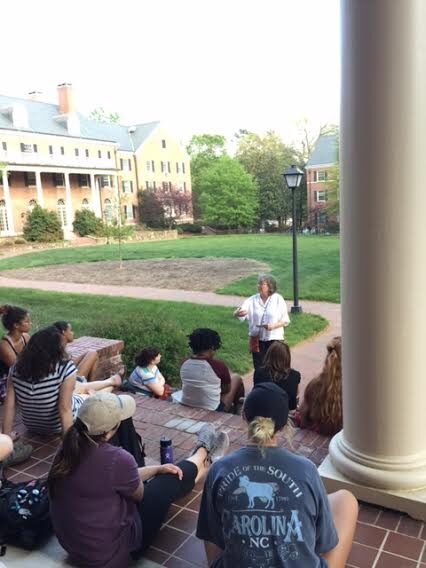

This afternoon my students in WMST 202: Feminist Thought and I had the great fortune to take a feminist geography tour of UNC's campus with Prof Altha Cravey, Associate Professor in the Department of Geography. To prepare for the tour, I asked students to read Cravey and Michael Petit's 2012 article, "A Critical Pedagogy of Place: Learning through the Body." This article, published in Feminist Formations, discusses how to use feminist geographic approaches to space and place to help students understand and develop feminist understandings of space. The authors use the built environment of UNC-Chapel Hill as a case study and speak about their own use of a field trip as a pedagogical method in the undergraduate classroom.

Cravey and Petit's article introduces students to the embededness of gendered power in UNC's campus, focusing on the ways in which female-gendered bodies were regulated through dormitories when the campus first became available to female students. The article introduces two area of campus: 3 dorms - Alderman, Kenan and McIver and the Spencer area which includes Spencer dorm and the president's house. Cornelia Philips Spencer Hall was built in 1925 as the first UNC dormitory for women; Alderman, Kenan and McIver, which sit in a U-shape around a grassy area, were built in 1937 and 1938.

We began our tour at Alderman, Kenan and McIver Halls, where students were able to appreciate the spatial use of a Panopticon, whereby women in the dormitories, and their visitors, could be viewed by anyone else in the area. This surveillance was aided by the large verandas that adorned the front of the dormitories and the nearly floor-to-ceiling windows that offered direct views into the ground floor parlors. During our tour, we discussed the use of Panopticons in institutions including schools and prisons and students struggled to understand the logic of the early 1930s when female students were both figured as worthy/needing of protection and yet placed in dangerous environments. For example, the 3 dormitories are rather isolated from campus, meaning that female students had to walk considerable distance to attend classes, movement that was hindered by the dress codes of the day. While noting that the logic concerning dress codes that deemed female figures as "distracting" were absurd, students nevertheless connected these ideas about the need to surveil and police female bodies to contemporary rape culture. Issues of gender and sexuality are implicated with race and ethnicity and Cravey and Petit stress that the small group of women who were admitted to UNC in 1897 "were a select group privileged by class status, wealth, and, most important in the Jim Crow South, whiteness" (108).

We then moved to Spencer Hall, the first woman's dormitory, built in 1925, which now abuts the busy thoroughfare of Franklin Street. As Cravey and Petit's article noted, Spencer was built literally in the shadow of the president's house and the president would have been able to look down on the inhabitants of the hall. Students noted that today Spencer sits between two patriarchal structures - the president's house and the Chapel of the Cross. Again, students recalled the physical marginalization that female students endured - they lived at the edge of campus and, prior to the construction of dormitories, had to rent rooms in houses off campus. In the absence of places to socialize and congregate, female students spent considerable time commuting to and from campus - going home to eat lunch and returning for afternoon classes, etc. If a female student left the university she had 24 hours not only to leave the campus, but the entire town of Chapel Hill (109).

This tour was a great way to embody feminist theory and pedagogy and to apply feminist analytics to environments that we may be intimately familiar with, but that escape scrutiny on a daily basis. Thanks to Prof Cravey and her work, we were all able to "consider the embodied experience of place" and connect UNC's campus and downtown Chapel Hill to "a constellation of processes and social relations that link locally, regionally, and globally in complex and unpredictable ways" (114).